Traditional Japanese sweets known as “wagashi” capture the essences of the seasons, historic customs, and the hopes of people. Dive into the world of wagashi in this special feature along with wagashi-maker, Hiroyuki Sanno.

Aesthetic morsels filled with tradition

What comes to mind when you think of Japan? Summer light filtering through green leaves? The moon reflected on a clear lake? Or perhaps Mount Fuji covered in cherry blossoms? These images of Japan have been written about and depicted through paintings throughout the ages, but they have also been captured in a beautiful, edible form.

wagashi (literally, “Japanese confections”) were the original sweet treats before the likes of snacks such as Pocky or Japanese KitKat. In fact, many wagashi can be found in Japanese groceries around Australia and include favourites such as mochi (rice cakes), dango (mochi dumplings), and manjuu (steamed buns with sweet fillings).

These sweets evolved from simple fruits into the intricate delights they are today during the Edo period in the ancient Japanese capital of Kyoto. They were served alongside matcha (powdered green tea) as a key component of Japanese tea ceremonies.

Tea ceremonies share an intimate connection with seasonal themes. As such, a host of one will choose elements to serve that capture the seasons. The wagashi presented are a reflection of the respect for the seasons, and evoke images of flowers, leaves, fruits, and natural scenery through their shapes and poetic names.

The connectedness to nature can also be found in the ingredients used to make wagashi as they have a tendency to be plant-based and seasonal. For example, spring wagashi may be cherry-blossom-flavoured with the abundance of cherry-blossom leaves in spring, whilst you can often find chestnut-based wagashi in autumn.

Wagashi encapsulate the fleeting nature of Japanese aesthetics through the combination of their ingredients, colours, shapes, aromas, and textures.

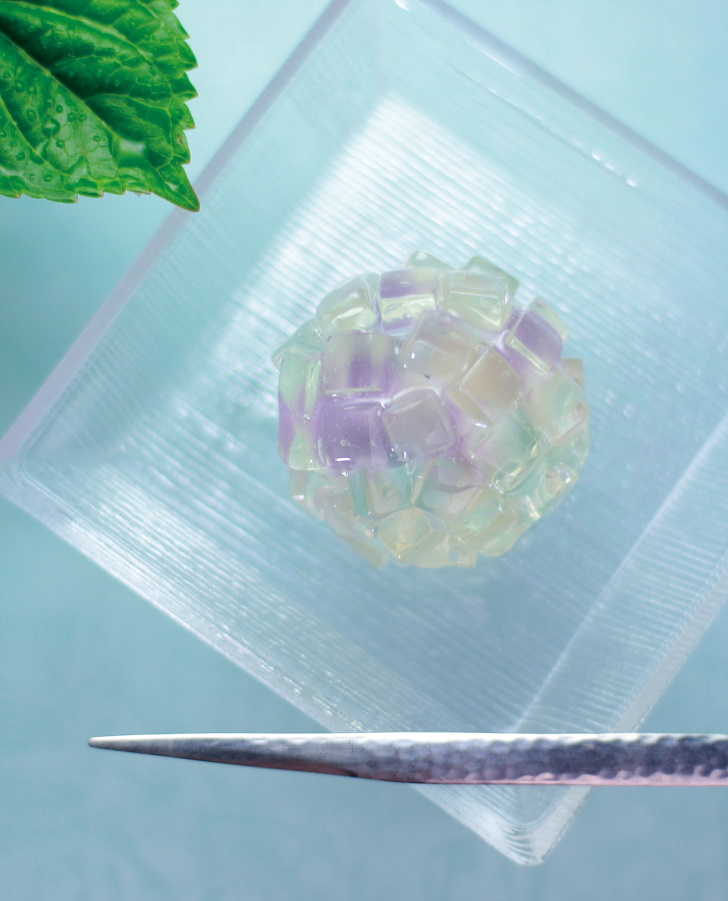

Aficionados of wagashi may be familiar with premium sweets known as “jonamagashi”. Each of these sweets is painstakingly made by highly experienced wagashi-makers and are known for their particularly close affinity with the seasons. jonamagashi are given a special “kamei” or “confectionery name” to capture the seasons, famous locations, or other traditions that the confection embodies. Allowing your mind to wander through the images these kamei conjure up is just one of the ways to enjoy jonamagashi.

Types of wagashi

Wagashi can be categorised into three different types: namagashi, han-namagashi, and higashi.

Namagashi is often what most people picture as the quintessential wagashi. They are fresh sweets often made from glutinous rice flour, or nerikiri (a dough with a sweetened bean-paste base) and best eaten on the day they are made. Namagashi served in summer months sometimes feature transparent jelly parts made using agar-agar or kudzu starch for a refreshing appearance.

Han-namagashi are less fragile and have a dry exterior. A popular example of these sweets is monaka, which is a sweet filling, often red bean paste, sandwiched between two crispy wafer shells.

Higashi are dried sweets such as rakugan—a mixture of rice flour and powdered sugar that is pressed into moulds to form seasonal shapes. Rice crackers also fall into this category.

A wagashi for every occasion

The giving of gifts across various occasions is customary in Japan and wagashi have their place as both gifts and seasonal delights to celebrate different festivals and events.

Hanabiramochi (or “flower-petal mochi”) is a type of wagashi eaten over New Year’s made of white and pink mochi that are flattened, pressed together, and then filled with sweetened miso and burdock root, before being folded in half. This mochi was eaten over the first three days of the year during the Heian period to celebrate the new year, and originated from “hishihanabiramochi,” which were hard rice cakes that were eaten when ringing in the new year to pray for longevity and prolong life in a ritual to strengthen the teeth (as teeth are said to symbolise age). Other red and white wagashi are also prominent during this time as the colours are said to be auspicious.

Hinamatsuri (also known as the “Japanese Doll Festival”) takes place on the 3rd of March every year and is where sakuramochi and hishimochi are often eaten. Sakuramochi is a pink-coloured, cherry-blossom-flavoured mochi filled with sweetened red bean paste and wrapped in a pickled cherry-blossom leaf, whereas hishimochi is made of pink-, white-, and green-coloured rice cakes stacked on top of each other and sliced into diamond shapes.

The 5th of May sees the annual tradition of Children’s Day where white rice cakes filled with azuki beans and wrapped in oak leaves known as “kashiwamochi” are eaten aplenty. In some regions of Japan, the filling is white bean paste. Chimaki, glutinous rice dumplings wrapped in bamboo leaves, are also eaten during this time in some households.

In the summer, refreshing wagashi such as mizu-manjuu, mizu-youkan, kuzukiri, and kingyoku are more prevalent. Summer wagashi not only look refreshing, but their smooth mouthfeel and clean flavours help to whet your appetite during Japan’s notoriously hot and humid summers.

Traditional Japanese wagashi embody the seasons, customs, and prayers of those who eat them as delicious works of art.

We spoke to Hiroyuki Sanno, a freelance wagashi artisan based in Japan who kindly provided the beautiful wagashi photos found in this special feature, and he offered the following insight about the wonders of jonamagashi.

Jonamagashi developed from and is deeply connected to the tea ceremony culture. It has been passed down as a tradition throughout the ages, incorporating the heart and culture of Japanese people. Jonamagashi is also known as “the art of the five senses” due to its appearance, flavour, and aroma, as well as the reverberations and deep meanings behind their names. While it goes without saying that the flavours are exquisite, I believe a big part of what makes jonamagashi so amazing is the artistic creativity born out of the combination of the artisan’s skills and sense.

Profile: Hiroyuki Sanno

Born in Aichi Prefecture, Hiroyuki learned the basics of wagashi-making at a long-standing wagashi shop in his home prefecture. He moved to Gifu Prefecture to ply his trade in 2007 after obtaining his Confectionery Hygiene Master license. In 2011, he became a certified First Class Wagashi Maker, won a number of national wagashi contests, and even worked internationally by holding wagashi-making seminars in Europe and China. He moved on to making original wagashi incorporating Japanese traditions and culture as well as modern aesthetics, and became a freelance wagashi maker in 2019. The younger generation has latched onto his creations posted on social media pages, with his official Instagram account boasting over 60,000 followers. Hiroyuki lives by the motto of bringing smiles to people’s faces through wagashi.

Instagram: @wagashi_sancha