Waka (和歌) literally means “Japanese poem” – Wa (和) is usually referred to “Japan” or “things Japanese” as in Washoku (和食) being “Japanese cuisine”, and Ka (歌) or Uta (歌) in modern times means “song”, though in ancient times it meant “poem”.

A brief history of Waka (和歌)

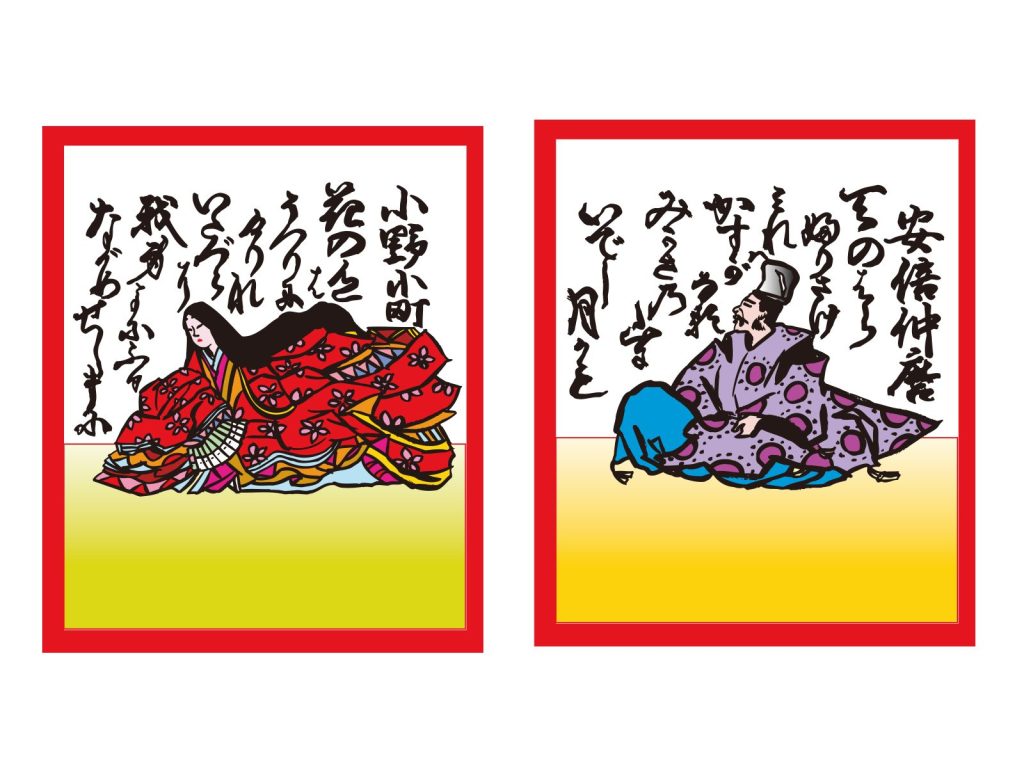

Japanese style poems were popular, even before the Chinese influence declined when Kentōshi (遣唐使, “Japanese missions to Tang China”) was abolished. They were enjoyed amongst the imperial court as well as ordinary people such as townsfolk, soldiers, farmers and woodworkers throughout the Nara (奈良) period (710-794) and the Heian (平安) period (794-1192). This is apparent in Man’yōshū (万葉集, “The Anthology of Ten Thousand Leaves”, the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry) which was allegedly compiled by a few poets of the time led by Ōtomo-no-Yakamochi (大伴家持) in c.759. People from all walks of life used poems as the means of expressing their various feelings such as hope, aspiration, sorrow, love and so forth. It is notable that people who wrote poems knew how to read and write Kanji (漢字, “Chinese char acters”). Kanji (漢字) was introduced to Japan around the late 4th or early 5th century, most likely through contact with the Korean Peninsula. With the spread of Kanji (漢字), Waka (和歌) began to flourish. Since then, Waka (和歌) has been a popular pastime and a part of the culture throughout Japanese history. All you need is a sheet of paper and a brush or a pen, or a smartphone nowadays to write down your own masterpiece. There are not only numerous professional poets but also ordinary people who enjoy Waka (和歌) as their favourite pastime in modern-day Japan.

Forms of Waka (和歌)

The term Waka (和歌) encompasses a few different forms of classical poems in Japan. All of them are based upon the mixture of five or seven syllable (or mora) phrases. It seems that five or seven syllable phrases sound pleasant to Japanese ears. For example, monologues and dialogues in the traditional Kabuki (歌舞伎) play were skilfully and surreptitiously written mostly in the combination of five and seven syllable phrases.

The first form of classical poems is called Katauta (片歌, “poem fragment”) which consist of the 5-7-7 form and it is one half of an exchange of two poems. It is the shortest form of Waka (和歌) . The second form of classical poems is Chōka (長歌, “long poems”). It consists of two or more 5-7 combinations, with a final 7 phrase added to end the poem. It is often accompanied by Hanka (反歌, “envoy poems”) to encapsulate the Chōka’s message. This style is mostly found in Man’yōshū (万葉集) mentioned above. The third form is called Tanka (短歌, “short poems”). It consists of 5-7 5-7 7 syllable phrases. This form has been the most popular style throughout the history of Japanese poetry. It is by far the most popular form nowadays. The fourth form is called Sedōka (旋頭歌, “memorised poems”). It consists of the repetition of 5-7-7 and it is often seen in a dialogue style called Mondōka (問答歌, “dialogue poems“) or an exchange between lovers, Sōmonka (相聞歌, “poem of love and longing”). The fifth form is called Bussokusekika (仏足石歌, “poems inscribed on the Buddha’s Footprint Stone – at Yakushiji Temple, 薬師寺) which consists of 5-7-5 7-7 (the same as Tanka) with another 7 syllable phrase added.

Amongst the various forms of Waka (和歌) above, it is obvious that what is called Waka (和歌) these days are Tanka (短歌). Because of the number of its syllables being 31, it is also called as Misohitomoji (三十一文字, poems containing 31 syllables in total).

Popularity of Tanka (短歌)

As mentioned earlier, Tanka (短歌) is still a popular pastime for many Japanese. When there is a friendly society or similar kind of organisation, there is a high probability that it has a Tanka (短歌) sub-group within the organisation. Members of the sub-group regularly meet, for instance once a month, and present their recent Tanka (短歌) in front of other members and enjoy comments and discussions. Some of those groups invite a professional poet to seek further advice or to have their poems assessed. They often compile their own “anthology of Tanka (短歌)” and have them printed as a booklet or upload them on various digital platforms.

Those who don’t belong to any groups may have an opportunity to send their Tanka (短歌) to daily newspapers (yes, actual paper “newspapers” are still popular in Japan!) or magazines which offer readers an opportunity to display their Tanka (短歌) with a Tanka (短歌) editor commenting on some selected Tanka (短歌) once a week.

Utakai-hajime (歌会始)

Utakai-hajime (歌会始) is the Emperor’s Waka (和歌) Meeting at the start of the year. It is not exactly clear when it started in the Imperial Palace, but it is alleged that there is a written record of it in 1267. Since then, it has been held irregularly depending on the Emperor’s interest in Waka (和歌). Since 1869, the year after the Meiji-ishin (明治維新, “Meiji Restoration”) took place, it has been held every year even when Japan was at war between 1941 and 1945.

Since 1946, the general public have been encouraged to send in their Tanka (短歌) to the Imperial Household Agency, Kunaichō (宮内庁), and if their Tanka (短歌) are selected, they are invited to the Imperial Palace to attend the Utakai-hajime (歌会始).

So, if you would like to meet the Emperor and the Empress in person at the Imperial Palace on New Year’s Day, why not write a Tanka (短歌) and send it to the Kunaichō (宮内庁), regardless of your nationality. The deadline for the application is the 30th of September this year. More details can be found at the website (https://www.kunaicho.go.jp/event/eishin.html).

Author

Shunichi Ikeda

BAS Hons (ANU)

MEd (SUNY at Buffalo)

Visiting Fellow, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific