Haiku (俳句) is a type of short form poetry with hai (俳) literally meaning funny, joke or jest and ku (句) meaning phrase, sentence or verse. However, it has been known in and outside of Japan as a short but elaborate form of poetry with at least three rules: it should consist of three phrases composed of 5-7-5 pattern morae (on 音), include kigo (季語 seasonal reference) and kire (切れcutting) or kireji (切れ字 cutting word). However, there are poems that do not conform to these rules, i.e., muki (無季 no seasonal reference) or jiyūritsu (自由律 not conforming to the 5-7-5 pattern) and the definition of haiku (俳句) varies between different Haiku (俳句) associations in Japan.

A brief history of Haiku (俳句)

As was covered in the previous Snippet #21, the Japanese have been enjoying creating poems based on 5 or 7 morae since at least the Asuka jidai (飛鳥時代 c. 7th century). This could be because this pattern sounds pleasant to Japanese ears, particular in the form of tanka (短歌), 5-7-5-7-7 morae.

In the middle of the Heian jidai (平安時代 c.10th century), so-called renga (連歌) became popular amongst poets. It is a peculiar style of poetry in that multiple poets create a poem in turn to produce a continuous and meaningful poem. The first poet creates a 5-7-5 poem called hokku (発句the beginning phrase) and the second poet adds a 7-7 phrase called wakiku (脇句 the following phrase) which should be relevant to the hokku (発句). Then the third poet contributes another hokku (発句) which needs to be relevant to the previous hokku (発句) and wakiku (脇句) and all poets present keep improvising poems in this manner. They enjoy the connections to the previous phrases and atmosphere. It became very popular during the Muromachi jidai (室町時代 14th–16th centuries). At the same time, haikai no renga (俳諧の連歌), a kind of a game based on the renga (連歌) style came into being with a flavour of satire and humour through a play on words in a more relaxed atmosphere. During the Edo jidai (江戸時代 1603-1868), this haikai (俳諧) became an independent genre, with renga (連歌) on the decline.

During the Meiji jidai (明治時代 1868-1912), poets such as Masaoka Shiki (正岡子規 1867-1902) advocated for hokku (発句) becoming independent of renga (連歌) and re-naming the genre as haiku (俳句) from haikai (俳諧). Therefore, the history of haiku (俳句) is relatively new.

Basic Rules of Haiku (俳句)

The first and foremost rule of haiku (俳句) is its style. It comes from hokku (発句) in renga (連歌) and basically keep the 5-7-5 morae style. You need to express your thoughts, originality, emotive feelings and so forth in these 17 morae. However, you are allowed flexibility in adding one or two extra morae, for example more than 6 morae on the 5 part or more than 8 morae on the 7 part, to complete your haiku (俳句). This is called jiamari (字余り extra letters).

The second rule requires you to use kigo (季語 seasonal reference). It doesn’t have to reference the seasons themselves, such as haru (春 spring), natsu (夏 summer), aki (秋) and fuyu (冬 winter), and any words suggesting or alluding to seasonal connotations would be accepted. For example, if you mention wattle flowers starting to bloom, it would be obvious that you are talking about spring in Australia. Another example is that when you use words like skiing or skating, readers would know you are talking about winter. The important aspect of this rule is that you express your sensitivities to the seasons through your impressions of natural phenomena.

However, as you might guess, there are a sizable number of haijin (俳人 those who create haiku 俳句) who advocate that kigo (季語) is unnecessary and you should be free from this rule. To this viewpoint, those who believe that kigo (季語) is essential say that haiku (俳句) without kigo (季語) shouldn’t be called haiku (俳句) and they should be called senryū (川柳 same style as haiku 俳句, but focusing on human nature and humour).

The third rule is to have an appropriate kire (切れcutting) or kireji (切れ字 cutting word). It is typically inserted at the end of one of the 5-7-5 phrases. A kireji (切れ字) works similar to the caesura in classical Western poetry. A kireji (切れ字) functions to mark rhythmic divisions. There are a few kireji (切れ字) and some of them briefly cut the stream of thought, suggesting a parallel between the preceding and following phrases, or they may convey a dignified ending, summarising the verse with a climactic effect. The three most common kireji (切れ字) are kana (かな), ya (や) and keri (けり) – although these particles are classical vocabulary, they are still used nowadays for poems.

As you might guess, there are haijin (俳人) who ignore the traditional effects of kire (切れ) or kireji (切れ字) and create poems with new techniques.

A few Haiku (俳句) to savour

Here are a couple of haiku (俳句), although they were called haikai (俳諧) during the Edo jidai (江戸時代 1603-1868), by famous haikaishi (俳諧師 they were called this way in their days and not haijin (俳人) as contemporary poets are called).

Matsuo Bashō (松尾芭蕉)

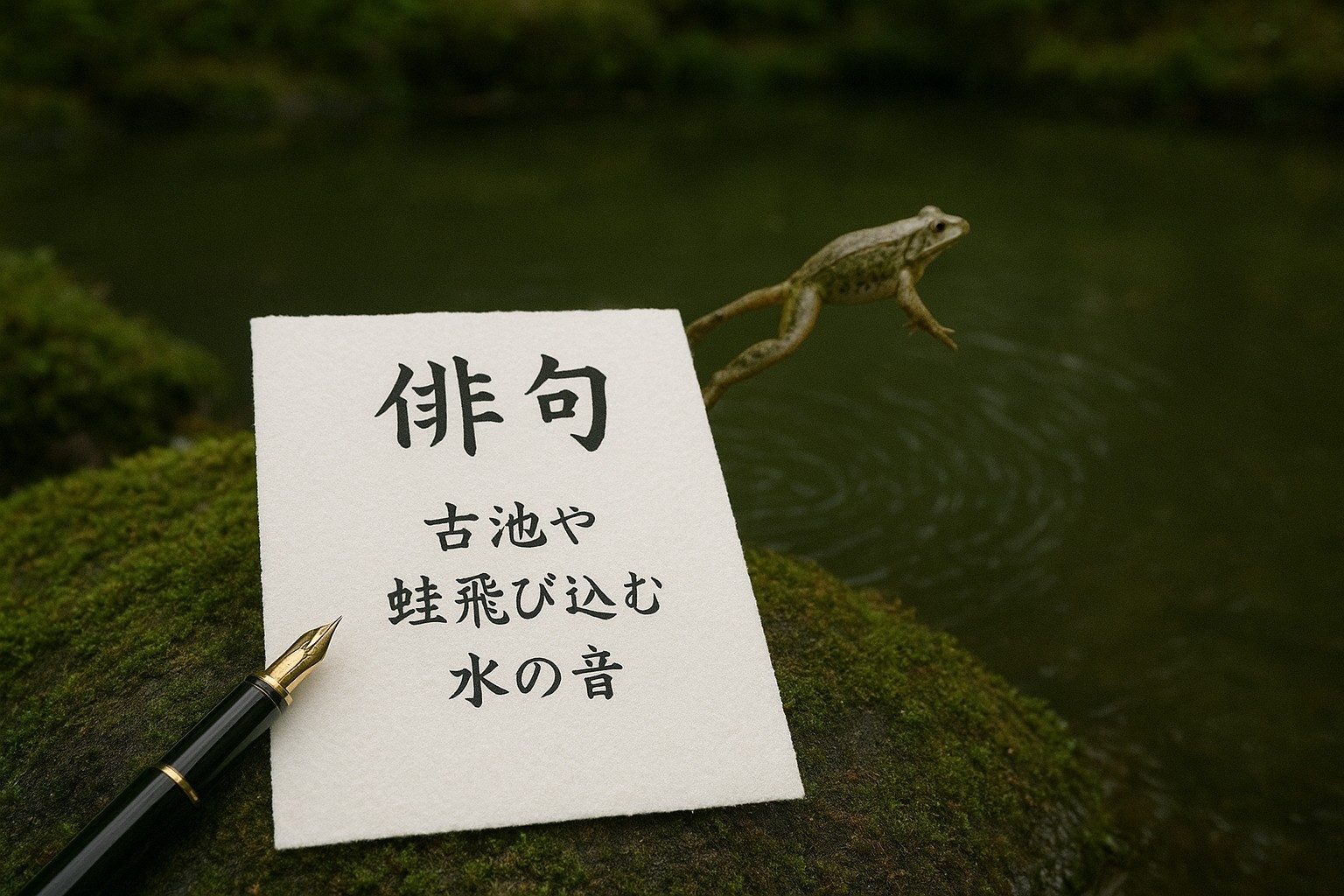

古池や 蛙飛び込む 水の音

(ふるいけや かわずとびこむ みずのおと)

fu-ru-i-ke-ya ka-wa-zu to-bi-ko-mu mi-zu-no-o-to

old pond

frog leaps in

water’s sound

Kobayashi Issa (小林一茶)

我と来て遊べや親のない雀

(われときて あそべやおやの ないすずめ)

wa-re-to-ki-te a-so-be-ya o-ya-no na-i-su-zu-me

come

play with me

little orphan sparrow

Author

Shunichi Ikeda

BAS Hons (ANU)

MEd (SUNY at Buffalo)

Visiting Fellow, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific