Koichi Takada belongs to a new generation of architects that strive to return nature to the urban environment. A refined Japanese sensibility informs the architectural designs of his practice based in Sydney, Australia.

Koichi Takada Architects is approaching two decades of operation, and Takada’s visionary, nature-inspired architecture has been widely awarded for his mission to encourage the next generation of architects to consciously shape the future of humankind.

Takada’s architecture reconnects humans to the natural environment, drawing inspiration from organic forms and local contexts. “Questioning the loss of nature in cities opens up new possibilities in architecture and design. In nature we find our ability to regenerate.” Koichi Takada

Koichi Takada is one of the most internationally recognised Japanese architects of his generation. Based in Sydney, his practice bridges Japan, Australia and farther afield, mediating between urban density and the natural world. For Australian readers, he reflects on formative moments, why “breathing space” matters in high-density cities, and how design can help us live well amid climate change.

─ Could you start by sharing how you first became interested in architecture—and how that interest took you overseas?

I chose architecture at about sixteen. Seeing Manhattan’s silhouette for the first time felt beyond human scale—an electrifying moment. More than buildings, I was fascinated by the city as a living organism, which took me to New York to study. Living there, I found the “concrete jungle” thrilling to visit yet demanding to inhabit. I later moved to London, whose smaller scale and gentler rhythm felt closer to the Japanese sense of proportion. After returning to Japan to train, I entered a competition linked to Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art. That invitation brought me to Australia in 1998 or 1999—just before the Olympics.

Discovering Australia

─Your first experience of Australia came through a competition for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, correct?

Yes. I remember stepping off the aircraft by stairs—no airbridge—and being struck by the clarity of the air and southern sun. I thought, “I could live here.” Sydney felt open and humane: the atmosphere, pace of life, and proximity to water and parkland offered a chance to practisearchitecture that respected nature while engaging a global city.

─ How did Sydney compare with New York or London at that time?

New York is the apex of intensity; thrilling but demanding. Sydney felt open. Before the Olympics, most towers were in the CBD; the harbour shaped daily life. There was a lightness—bare feet, parks and shorelines within easy reach. I often use “breathing space”: pockets of relief where people slow down and reset their senses. Those intervals are social infrastructure.

─ Sydney has grown taller and denser. Do you sense a slide towards the New York environment?

Inevitably. By 2050 about seventy per cent of people will live in cities, pushing vertical growth. Up to roughly thirty storeys you still feel connected to the street—the human realm. Above that, the relationship with the ground fades and buildings risk abstraction. Our task is to make tall buildings that still foster connection and everyday humanity—places where neighbours meet rather than pass like strangers in the lift.

─ What is your approach in recent Australian residential towers?

I design for social life, not just private units. In Brisbane’s Upper House the best views aren’t locked in penthouses; the top is shared amenities. One level focuses on wellness—a gym, recovery rooms, genuine places to rest. Above that is the social level: a cinema, karaoke, generous rooms for gatherings. Put the most desirable spaces where everyone can enjoy them and people will come.

─ Many towers include amenities that remain empty. What makes the difference?

Hardware without software isn’t enough. You design the program: happy hour with a real bartender, hands-on art workshops, seasonal festivities like children’s Easter egg hunts. These rituals build community. It’s akin to hotel thinking—service is part of the architecture. We also invite small businesses to operate upstairs, bringing local enterprise into the vertical village. In Brisbane we partner with operators who understand neighbourhood culture; the tower becomes an ecosystem, not a sealed object.

Australia and Japan, Two Ways of Building

─ How do Japan and Australia differ as environments for design?

Japan’s limited land and high density turn architecture inward. You begin with the interior, then negotiate privacy and neighbours. Screens, shoji and graded transparency modulate views and light. Australia is almost the opposite: vast land, dramatic landscapes and a lifestyle opening directly to the outdoors—the house extends to garden, pool, and barbeque. In Japan you often create a complete world inside a box; in Australia you open the box to the sky.

─ And the role of natural disasters?

It shapes everything. In Japan you design with earthquakes, typhoons, and tsunamis; waterfronts are constrained and structures highly resilient. Australia is more fortunate in major cities, permitting a more direct dialogue with nature. But freedom brings responsibility—respect Country, ecosystems and change over time. Good Australian architecture is open yet carefully tuned to climate, orientation, and community.

Japanese Traditions Worth Seeing

─ For Australian readers travelling to Japan, what should they look for?

Timber. Traditional wooden construction embodies centuries of craft in proportion, joinery and surface. In Kyoto, temples and gardens present complete worlds in miniature. A small plot can feel infinite when scale and material are handled with care. Visit stone gardens such as Ryōan-ji to experience stillness; notice paths guiding you through shifting scenes. Seasons matter—blossoms, autumn foliage, snow— shaping how space is felt. Architecture is a stage for seasonal rituals. You mentioned the Osaka–Kansai Expo’s timber ring. Why is it significant? The great ring uses traditional carpentry akin to pegged connections—echoes of Kiyomizu-dera’s stage. It shows how past and future can meet, reconnecting craftsmanship with public life.

─ Which architects have most influenced your thinking?

Tadao Ando and Kengo Kuma. Ando’s concrete is precise yet human; panel grids often follow tatami proportions, embedding a Japanese measure in modern material. His handling of light—bright and soft, like sunlight through leaves—creates calm interiors. Kuma explores a “weaker” architecture: lighter, porous, returning to timber and craft. Both integrate the past into the present. I also urge visitors to walk Meiji Jingu’s forest in Tokyo; Kuma’s museum there is almost invisible until you notice the delicate layering of timber.

Respect and “Ma”

─ If you had to summarise your philosophy in a few words, what would they be?

Respect, and “ma.” Respect for nature and people—for communities, First Nations culture, history. And “ma,” the interval: the pause that lets you breathe. Digital life compresses time; architecture can reintroduce slowness—places to linger, notice light across a wall, hear wind in a tree. In practice this means thresholds, courtyards, verandahs and edges where nothing “commercial” happens but everything happens for human connection.

“The question is how to design a sustainable future people actually want.“

─ Could you share an example where this idea guided a project?

Norfolk in Brisbane was inspired by a pine cone. Beside a national park and a golf course, it offers an escape for people from Sydney or Melbourne. Not every project must be monumental. Norfolk works because it gives residents a genuine change of pace: sheltered balconies, shaded paths, garden outlooks—a quiet threshold that slows you down naturally.

─ Looking forward, what is the greatest challenge for architecture?

Climate change. Seasons are shifting worldwide. The question is how to design a sustainable future people actually want. One concept is the Sunflower House in Italy: petal-like roofs rotate to maximise solar gain, improving efficiency, while spaces orient to shade or warmth. The aim is self-sufficiency in energy and water—and comfort, a home attuned to daylight and weather.

─ Some argue sustainability is mostly about technology. You speak about rhythm and experience. How do these connect?

Technology is essential, but lifestyle is deeper. My grandparents rose with the sun and slept soon after nightfall. If architecture helps us reconnect with daylight, breezes, gardens and parks, technology can support living that is efficient and humane.

On Tall Buildings and Human Scale

─ Returning to high-rise living: is there a threshold where height undermines community?

There isn’t a single rule, but up to about thirty storeys you can maintain a felt connection to street life. Beyond that, it takes deliberate design to keep people engaged—with the city and with one another. That’s why we move shared amenities to the top—views become social catalysts. When people share the best part of a building, they begin to share their lives.

─ Finally, what advice would you give to young architects and designers in Australia?

Travel with your eyes open. Learn from landscapes as much as buildings. Respect Country and local communities. Embrace craftsmanship—the details of how things meet. And always design for the human experience at ground level: the threshold, the footpath, the bench in the shade.

─ What would you like readers in Australia to take away from this conversation?

Cities are not machines; they are places for people. As we grow taller and denser, we must also grow wiser—preserving breathing spaces, deepening our relationship with nature, and designing for community. If architecture helps us slow down and live well together, the future is hopeful.

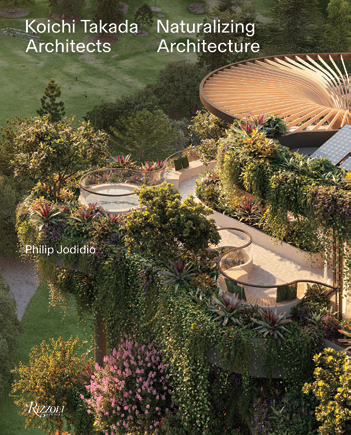

Koichi Takada Architects: Naturalizing Architecture — Rizzoli New York

By Philip Jodidio; A 240-page showcase of 15 global projects—from private houses to high rise “living” towers—advancing Takada’s nature-driven urban vision.